The Bedrock of the Budget Process

A Solid Foundation and its Initial Investment

Local governments need to establish a solid foundation for an effective budget process. This can be achieved through 6 key elements, which we will discuss in this section of The Process of Budgeting as Envisioned by Rethinking Budgeting. The Bedrock of the Budget Process puts in place policies and practices that encourage savvy and wise decisions during the budget. This foundational approach not only ensures fiscal responsibility but also promotes transparency through clear policy boundaries and by addressing when and where public engagement should be considered. While the bedrock requires an initial effort to establish, it can be maintained at a fraction of the cost in the years that follow.

It is important to note that once established, this "bedrock" does not need to be completely re-built each year. Instead, it requires an initial investment of time and energy to create and can then be maintained and adjusted with less effort in subsequent budget cycles. By focusing on these key elements, local governments can improve decision-making, foster a more strategic budgetary approach, and ultimately strengthen their financial management practices over time.

Six Elements of the Bedrock

Local governments need to establish bedrock for an effective budget process.

1. Strategic Planning

Strategic planning in public budgeting begins with accepting uncertainty and clearly defining the problem before developing solutions. By introducing constraints, it maintains focus on the most critical issues, avoiding the risk of spreading resources too thin. A rolling planning process ensures strategies remain relevant and responsive to changing conditions, while collaboration and fairness are essential for gaining broad community support and ensuring successful implementation.

Read more

2. Develop a Service Baseline

A service baseline in budgeting involves creating an inventory of all services provided by the government, including details such as cost, performance, and service demand. This allows for more meaningful budget discussions by highlighting the actual services offered, bridging organizational silos, and identifying trade-offs between services. A detailed service inventory can also help reveal redundancies, inefficiencies, or areas where service levels can be adjusted to better meet community needs.

Read more

3. Set Policy Boundaries

Financial policies provide essential boundaries for local government budgeting. Key policies include maintaining sufficient reserves, using one-time revenues only for one-time expenditures, and setting user fees to cover service costs. A structurally balanced budget should match ongoing revenues with expenditures, while long-term financial planning and a consolidated budget process promote transparency and can include public engagement.

Read more

4. Set Boundaries with Long-Term Financial Planning and Forecasting

Long-term financial forecasting helps identify risks and provides a more comprehensive view of future revenue and expenditure trends. Key principles for effective long-term planning include institutionalizing forecasting, setting a time horizon tailored to specific needs, and considering the full scope of government funds. The plan should include risk assessments of debt, pensions, infrastructure, and other potential disruptions, while linking to other long-term planning processes like capital investment or land use.

Read more

5. Develop the Capacity for Public Engagement

The budget officer must design a budget process that: 1) considers trade-offs in how resources will be used; and 2) builds or maintains the legitimacy of the local government in the eyes of its stakeholders. High-quality public engagement can support both objectives. Investing in skills development and collaborations with other departments or external resources like universities and consultants can help improve public engagement.

Read more

6. Build Networks with Outside Organizations

Local governments may not be able to tackle complex community challenges alone due to limited authority, resources, or capacity. By building networks with public, private, and nonprofit organizations, local governments can leverage additional resources to solve problems more effectively. Forming these networks is an advanced aspect of public budgeting and requires teamwork beyond just the budget officer’s role.

Read more

1. Strategic Planning

Strategic planning in public budgeting embraces uncertainty, defines problems before solutions, and maintains focus by introducing constraints.

Accept Uncertainty

Strategic planning is a long-standing “best practice” in public budgeting. This is for good reason, as it is important to think strategically and long term in a volatile and resource-constrained environment.

A good strategic planning process focuses participants on the future and how they might shape it to increase community well-being. It does not focus on producing a detailed planning document because the document becomes obsolete when the world changes. Key design principles for strategic planning begins with accepting uncertainty.

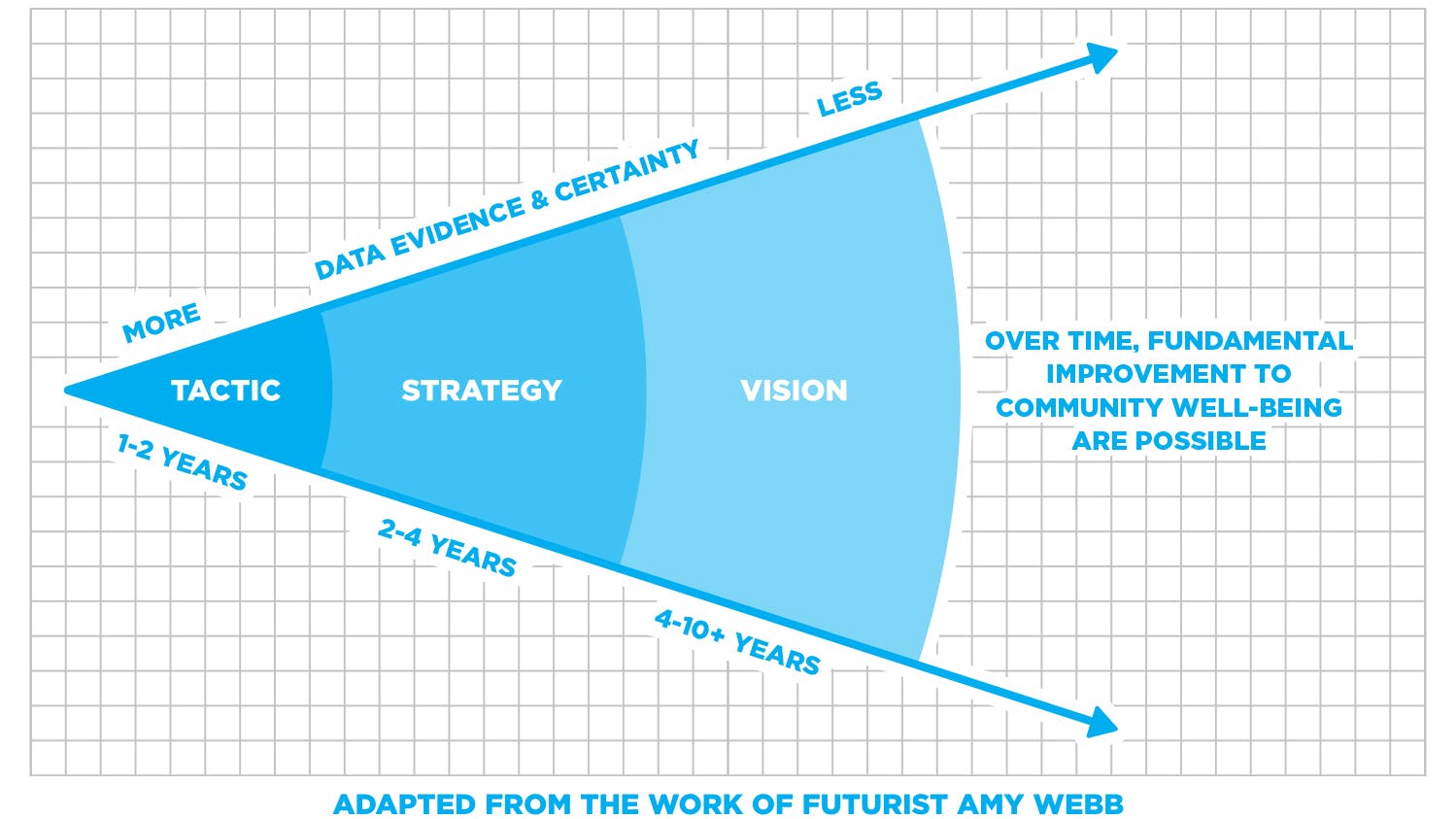

The approach to planning and strategy must be to accept our limited knowledge of the future. This idea is expressed by the “time cone” The left end is closer to the present where the near future is more predictable. To the right is the far future, which is less predictable. The time cone shows us that tactics, strategy, and vision are simultaneously part of strategic planning but receive different emphasis based on how far you are looking into the future.

The vision is what the future might look like in response to specific actions. It is an aspirational state for the community. It should be broad enough that it has room for changes in strategy. For instance, when elected officials change, the strategy may need to shift. At the same time, the strategies should not be so broad as to be meaningless. To illustrate, a community vision might call for: 1) reducing street-level violence, as measured by homicide or aggravated assault rates; or 2) an increase in park facilities, as measured by capital improvement expenditures per park. Either of these could be broken down to measure how different neighborhoods or populations are doing.

Strategy defines how the organization will achieve the vision. Two to four years is a proper time horizon for strategies because the future beyond two years is too fluid for tactics to be feasible. We use four years as an outer limit to correspond with the typical term of office for elected officials. For street-level violence, the strategy might be to prevent violence by identifying and interrupting the vectors along which violence starts. For example, in some communities, perceived slights or insults can escalate to deadly violence. For increases in park facilities, capital improvements construction typically can be started in two or four years, which accommodates planning, community feedback on the design, etc.

Tactics are appropriate where there is certainty about the environment—typically one to two years into the future. Examples might involve implementing new programs, abolishing obsolete or unaffordable programs, or fine-tuning existing services. Tactics have a direct connection to the budget but are not synonymous with it. Tactics are putting the strategy into action. Some actions may not fit neatly in the budget. For example, perhaps a tactic is to make an adjustment to an existing program, and that change can be done with existing staff and resources. This may be less of a budget discussion and more of an issue of day-to-day management. To show what tactics look like, let’s continue with our examples of preventing violence by identifying and interrupting the vectors along which violence spreads and building a park. For violence interruption, 1) detecting and interrupting potentially violent conflicts; 2) identifying and treating people who are at high risk of committing violence; and 3) mobilizing the community to change norms. For a park, tactics might include: 1) identifying high need areas for new capital investment; 2) assigning a planning and engineering team to meet with the public for input; 3) a plan proposal; 4) bid development and award; 5) construction; and 6) a public opening ceremony.

Define the Problem Before Defining the Solution—Then Develop a Savvy Strategy

As part of strategic planning, local governments often face complex problems like degradation of the natural environment, increasing economic opportunities, drug addiction, and more. Strategic planning should define the problem, seeking to identify the root causes. This makes it easier to find strategies with the best chance of working. To illustrate, our earlier examples had to do with street-level violence. If a community’s most important challenge with violence was domestic violence, then the solutions would look very different.

This sets the stage for a savvy strategy—one that addresses the right underlying causes of the problem, has a coherent underlying logic for how the problem will be solved, and defines what success looks like in a way that success, or lack of, can be verified later.

Provide Focus by Introducing Constraints

A risk in strategic planning is trying to cover too much. For example, there may be a belief that every department must be covered in the plan. Or there may be many issues facing the community with a wish to address them all. However, a local government only has so much capacity to act. A planning process needs to identify the most important strategies and the ones that give the local government (and its partners) the best chance for success. You can provide focus by introducing constraints on what the strategic planning process will consider. Constraints can be a filter to remove some strategies from consideration and highlight trade-offs between different strategies. For example, outside mandates from higher levels of government could be considered a constraint.

Effective strategy considers the assets available, starting with fiscal resources but also including community support, staff expertise, and elected official support. There will always be some limit on the assets available, which forms a constraint.

Veteran budgeteers may wonder how a focused strategy could serve as a filter for deciding where to allocate money in the budget. If strategies should be focused on a limited number of critical problems, then much of the local government’s operations will not be related to the strategy. If that is the case, how do you evaluate budget requests, many of which will concern operations that fall outside of the strategic focus? First, if a strategy is focused, it helps identify the most valuable budget requests. It helps prevent “strategic alignment” from becoming a box-checking exercise, where every request is related to the strategy in some way.

That said, local government will always have responsibility for day-to-day services, and those services may not necessarily be “strategic.” Budget requests that do not support the strategy could be evaluated on their potential for maintaining acceptable standards for day-to-day services. We’ll have more to say on this in the section on service baselines.

Develop a Rolling Planning Process

Strategic plans should: A) welcome adjustments based on recent experiences; and B) avoid over-specifying long-term goals that may be made obsolete by changing conditions. Further, the time cone tells us that strategy cannot be viewed as a straight line. Rather, adjustments will need to be made to respond to changing conditions.

A rolling planning process should precede budgeting to update strategies and tactics. The goal is not to produce a new “strategic plan” but to guide the budget process about where resources should be allocated. A rolling planning process could become burdensome if it tries to do too much. It only needs to guide what to fund in the budget and make sure that the strategies stay relevant to changing realities. With that in mind, the goals of a rolling plan are twofold.

First, refine the strategies to consider the changing conditions and priorities. Perhaps conditions have changed such that your underlying assumptions are less certain or more certain. Or maybe there are new opportunities or problems to be considered. An example of the former might be a new grant that makes a strategy more cost-effective than it was before. An example of the latter might be that one of your strategies is not producing the results you thought it would.

Second, confirm the tactics that will be addressed in the budget. This should flow from your refined strategies. For example, if strategic planning suggests a certain program has potential to reduce street-level violence, then the budget should provide funding for pilot programs to try the strategies and for continued funding if the pilots prove successful.

Make Sure Planning is Collaborative

For planning to have a positive impact, it must be collaborative. The reason is simple: If people are involved in planning, then they are likely to be committed to the strategies that planning produces. If they are simply handed the strategies and told “do it,” then their commitment may be half-hearted. Further, bringing multiple viewpoints into strategic planning offers the best chance of accurately defining the problems the community faces and identifying solutions.

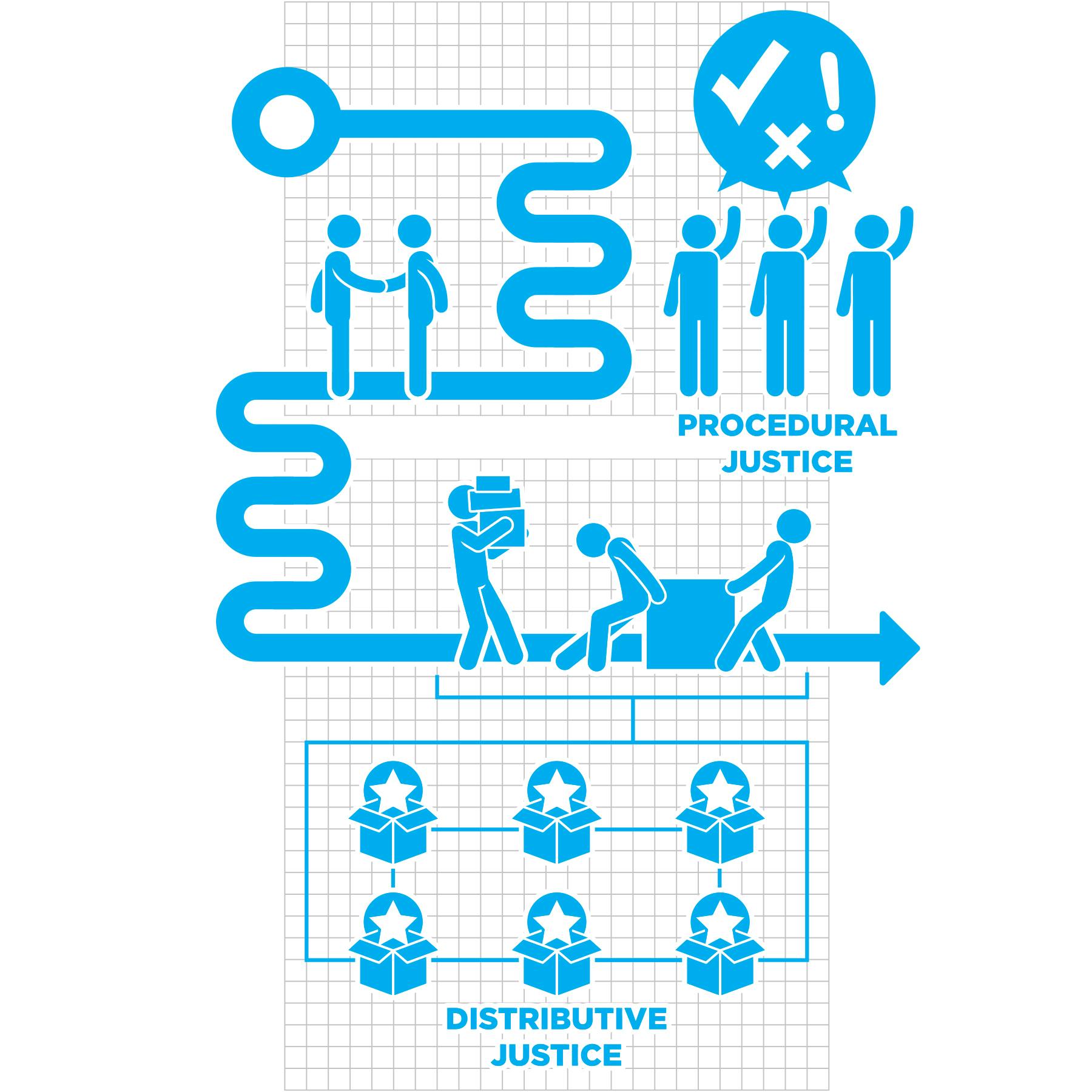

Make Sure Planning is Fair

If the process is not perceived as fair, the resulting plan is less likely to receive support. The two core elements of fairness are procedural justice and distributive justice.

Procedural justice concerns whether the process is perceived as fair. Consider questions like: Are the decision-makers being objective and neutral? Is it clear how the process works? Are participants treated with dignity, and do they have a voice? Procedural justice is critical because people are more likely to accept a decision or action that goes against their self-interest when they perceive that the process that led to the decision was fair. This is critical if a local government is going to succeed in limiting the scope of the plan and keep a broad base of support for it.

Distributive justice concerns how resources are allocated. This might concern which departments or parts of the community are getting resources because of the plan. This does not mean that resources should be evenly spread across all departments and/or neighborhoods to be “fair,” but it does say that local governments must be mindful of how the distribution will be perceived. For example, if planning is focused on certain issues, some departments will have a greater role in the strategies than others. A possible solution is to create an opportunity for cross-departmental strategies and tactics. Not only will this counteract feelings of unfairness because it opens possibilities for more departments to get involved, but it will also likely generate better solutions. Let’s consider our example of street-level violence. Cities that have used the approach will often involve the public health department, not just the police department.

How the budget is distributed to different parts of the community could be an issue. Some parts of the community may be consistently underserved. This could be addressed by separating the vision and strategies to focus on geographies or populations. For example, if a school district’s vision calls for improved graduation rates, then focusing on specific schools, income groups (children in poverty), or other issues behind graduation rates could be a powerful strategy.

2. Develop a Service Baseline

A service baseline creates an inventory of government services, detailing cost, performance, and demand, to support more transparent budgeting and identify inefficiencies or service trade-offs.

If a strategic plan is to be focused on a small number of critical issues facing the government, a budget must still address the other public services that make up total spending. Departments (e.g., fire, police, public works) provide a sense of the services a government provides. However, departments often do not communicate what services are provided. For example, it may not be obvious that services as diverse as road repair, snow removal, graffiti removal, tree services, and maintenance of public buildings are provided by a public works department.

Thus, establishing the bedrock of the budget should include developing a service baseline. This is a listing of the services provided, along with information about the services, like cost, performance, and more.

Like other parts of establishing the bedrock, developing a service baseline requires an initial investment of time and energy but can be maintained and adjusted year-to-year for a smaller investment. A service baseline is a wise investment because it allows budgeting to be more meaningful. Decisions can be made about specific services or programs rather than just about departments or divisions. The benefits of including program or service information in budgeting include:

- Transparency. Show what the government does and how much it costs in a way that is meaningful to people who are not familiar with the activities of departments. Budget discussions about police patrols and tree services, for example, are more meaningful than discussions about salary, benefits, commodity, and contractual service costs in the budgets of the police and public works departments.

- Bridging organizational silos. Clarity around programs and their purpose helps identify where multiple parts of the local government are part of the same service effort. Examples are traffic safety, which involves police, road maintenance, and traffic planning; and development, which involves fire, land use, and public works personnel to complete activities like plan reviews, inspections, etc. Recognizing these shared responsibilities between departments could invite new ways of delivering the service.

- Trade-offs. A service baseline provides for meaningful discussions about making budgeting trade-offs among services. When there are no new revenues, and if the budget for police patrols is to be increased, then the budget of another program, like tree services, will need to be reduced. Imagine a local government needs to find a way to reduce spending. The traditional line-item approach may invite decision-makers to arbitrarily reduce spending because the implications of cuts will not be clear. For example, the consequences of cutting the “equipment” line item in the public works department may not be obvious. A more productive use of decision-makers’ time might be to discuss whether the community can live with a combination of less tree services and road repair for the year, and then leave it to professional managers to decide how to allocate equipment spending. Notably, reaching better decisions from service/program information does not require a complex analysis. Simple framings, like how many people are served by one program versus another, can help reach better decisions.

- Sourcing. This allows for meaningful comparisons to other service providers when considering options such as outsourcing or sharing services with other governments.

Identifying all the services/programs a government provides requires an investment of time and energy. A program/service inventory can take place at several levels of detail. The most basic inventory is a list of program names and descriptions of what the programs do.

Beyond that, a program/service inventory could include descriptive features of the service and characteristics of the program that can be adjusted to modify service cost and performance. Such features include but may not be limited to:

- The external (or self-imposed) mandates governing how the service is provided. This could include contractual requirements (e.g., labor agreements) as well as professional “best practices.”

- How many people or customers are served. Is the service for the entire population of the jurisdiction or a subset?

- The extent to which the clientele for a program must rely on government for the service. Are there other places to get the service?

- Whether demand has been increasing or decreasing over time.

- The cost of the service.

- The revenue the program produces (e.g., user fees). To what extent do the revenues cover the costs of the service?

- The performance measures demonstrating efficiency of the program with its resources, how satisfied clientele are, and/or how effective the program is at achieving its purpose.

- Data from third-party studies on program effectiveness are becoming more widely available. The Results First Clearinghouse is a good example. A program inventory could show what third-party studies have found on program effectiveness, where study results are available. If outside research suggests that a given program is not effective, it may call into question if continuing to fund that program is the best use of resources. If research suggests a program is effective, then it may suggest the government emphasize rigor in program implementation in order to realize the program’s potential.

- Whether the service responds to needs in an underserved community.

The National Association of Counties provides a guide to conducting a program inventory that could help any local government get started.

A government’s current portfolio of programs should not necessarily be considered the “baseline.” The program attributes we described can provide insight into the level of service provided to the public and help local governments determine where services are adequate, need to be improved, or can be scaled back. This allows a government to make an intentional determination of its baseline level of service.

Even the most basic service inventory can support better decisions about service levels. For example, it is common for governments to discover from an inventory made up of a list of service names and descriptions that duplicative services are being provided by different departments. This may provide opportunities to establish greater coherence between the activities of different departments or to identify unnecessary redundancies.

Additional detail can enable better decisions. An inventory that catalogs and validates service mandates might reveal instances where the requirements of a mandate have been exaggerated beyond what the mandate requires. This discovery might open up options for how to provide a service or how to use the resources that have been allocated to that service previously. An inventory that addresses program performance might reveal opportunities to increase or decrease levels of service to better match what the community wants or can afford.

A government can start with a basic program inventory and add attributes as the opportunity arises and time and energy allows. The service baseline can also be adjusted as the community demand or need for services change.

A service baseline supports making better budget choices. We will have more to say about how budgets make choices later in this series.

3. Set Policy Boundaries

Financial policies set boundaries for budgeting, such as using reserves wisely, ensuring fees cover costs, and aligning revenues with expenditures.

Local governments should place boundaries on budget decisions with financial policies. Here is a summary of important financial policies for local governments and the key boundaries each policy should define.

Reserves

- The size of the fund you should maintain. Define the size of the reserve fund that is sufficient for the risks that reserves are meant to guard against, such as natural disasters or economic downturns. Define a range consisting of a minimum and maximum amount that reserves will strive to remain within, where that range is based on the risk the government is exposed to.

- The conditions under which reserves can be used. Reserves should not be used for ongoing expenditures, except as a temporary measure to get through extraordinary circumstances. A policy, for example, might limit use of reserves to maintaining service levels through an economic downturn or responding to an extreme event.

- Define commitments for replenishing reserves if they are used. This includes outlining how/when funds will be deposited into the reserves. For example, perhaps one-time or windfall amounts of revenue would be used to build up the reserve is it is below the minimum acceptable amount of reserves.

Revenue

- The use of one-time revenues. One-time revenues should only be used to fund one-time expenditures. A policy could go further by addressing volatile revenues. Extraordinary gains from these sources could be treated as one-time revenues. A policy could recognize exceptions for allowing one-time revenues to support on-going expenditures during economic downturns, as long as there is a plan to maintain long-term structural balance.

- Covering costs with user fees. A policy should define the extent to which services are expected to cover their costs with the fees charged to users. This is to avoid unintended subsidization of a service when a fee does not cover as much of the cost as it should. A policy should also direct that the fee be kept current with the cost of providing the service. That said, there may be cases where a fee is not meant to cover the costs of a service or where fees are not a suitable financing mechanism. A policy should recognize these cases too.

Budgeting and Financial Planning

- Definition of a structurally balanced budget. Local governments are often subject to legal requirements to have a balanced budget, where sources equal uses. However, such a budget may not be balanced over the long term. For example, if reserves are used to pay for ongoing expenditures, then they will eventually run out. A policy can provide for a more rigorous, local definition of a balanced budget, where ongoing revenues are matched with ongoing expenditures. A policy should also recognize role of long-term liabilities, like pension debt. A policy could direct that a “balanced budget” is one where contributions towards benefits already accrued as well as new benefits earned in the current fiscal year are being sustainably funded.

- Consolidated budget. The budget process should be inclusive of all funding available to the local government. If some funding is exempted from the scrutiny of the budget, then, at best, there will be lost opportunities for synergy. At worst, dysfunctional funding “silos” could develop, leading to duplicative and wasteful spending. A non-obvious example is spending requests made outside of the normal budget cycle, such that they avoid comparison to other options to use limited resources. That said, large governments in particular, may need to consider if a fully consolidated budget would be worth the additional complexity and administrative burden. A reasonable alternative to a fully consolidated budget might be to identify those areas that would benefit most from a consolidated approach and define those as minimum number of participants in a consolidated approach.

- Long-term planning. A policy should commit the local government to producing a long-term financial plan and a forecast for its operations. Long-term planning and forecasting are discussed in more detail later in this document.

These are the most universally salient policies to the operating budget. There are other policies a government should consider adopting to support financial management, such as debt policies or policies for long-term capital planning.

You can access information about the policies described in this section, and more, in the GFOA book Financial Policies. You can also download policy examples from local governments as part of the Financial Policy Challenge.

There may also be policies a government may wish to adopt to put boundaries on the budget that go beyond financial management. For example, there could be a policy about engaging the public in important decisions or using the budget to serve communities in need.

Finally, state governments can benefit from research conducted by Pew Trusts. Many of Pew Trust’s recommendations for states are aligned with the recommendations GFOA has made here in this series.

4. Set Boundaries with Long-Term Financial Planning and Forecasting

Long-term financial forecasting helps governments identify risks and future trends by setting tailored time horizons, assessing key financial risks, and linking to other strategic planning processes like capital investment and land use.

When decision-makers develop and approve an annual or biennial budget, they have drawn a temporal boundary; decision-makers will only consider public finances one or two years in the future. However, some decisions a government makes will have large implications over the long term. Long-term financial planning and forecasting provide insight into the long-term impacts of budget decisions and expand the temporal boundaries for good decision-making. This is done by showing the long-term trajectory of revenues and expenditures and by analyzing key financial risks, the consequences of which might not be apparent in an annual budget. Key design principles for long-term financial planning and policies are:

Institutionalize long-term planning and forecasting. Policies should formalize the use of long-term forecasting and planning. Policies should specify the time horizons that planning and budgeting will consider.

Identify a minimum time horizon but customize it to current needs. Many governments used five years as a minimum time horizon for long-term planning/forecasting, but the length should depend on the issues that challenge the local government’s financial condition. For example, if a local option tax that provides 25% of local revenue is scheduled to sunset in six years, a five-year plan and forecast might not be useful. Or, perhaps there are important foreseeable economic, demographic, and/or technological factors that will meaningfully impact revenue or expenditures in the long-term. The forecast should be of a sufficient time horizon to help the local government plan for these.

Identify a minimum scope but be open to looking beyond the general fund. The scope of a long-term financial plan can span from the general fund to the entire government. The interrelationships of a government’s funds influence which funds are included in the plan. For example, if there are material interfund transfers between the general fund and other funds, then the plan’s reach should include these other funds. Consider developing time horizons for different parts of the plan. For example, capital intensive operations might require a longer time horizon.

Identify a manageable frequency for planning. It may not be necessary to do a long-term financial plan and forecast every year. It might be wise to do a comprehensive financial plan every few years and a streamlined update to go along with the budget. Each update should show how the government is doing in its efforts to achieve and maintain structural balance calculations and explain the direction in which government is trending.

A plan that includes more than a forecast. A forecast is a necessary component of a long-term financial plan, but a forecast alone is often not enough. A long-term plan should provide a narration that explains why the government’s financial trajectory is headed in the direction it is. This helps elected leaders understand potential problems and possible solutions.

The financial plan should also identify risks to the financial condition and may need to include an analysis of those risks. Particularly important examples include:

- Long-term debt. High levels of indebtedness relative to ability to repay and backloading of debt repayment schedules are examples of risks that should be highlighted.

- Pension liabilities. The long-term financial plan should have projections of employer contributions based on current policy and expected investment returns. In addition, municipal governments that administer their own pension benefits should also consider incorporating risk analysis and pension stress tests that show the same forecasts for potential costs under different future investment and economic scenarios and other changes in plan assumptions (e.g. demographic shifts, inflation, etc.).

- Infrastructure. A long-term financial plan should reference a comprehensive asset inventory and management system. This should include an assessment of accumulated past unmet infrastructure preservation needs and annual future spending on capital maintenance needed to maintain infrastructure in a state of good repair.

- Other risks. A long-term financial plan should raise risks that could disrupt the local government’s finances. The plan should identify and assess the financial implications of risks arising from demographic, environmental, and technological shifts sources. Examples include aging populations, exposure to natural catastrophes, or exposure to cyberattacks.

Look for important links to other long-term planning processes. A local government often has several kinds of long-term plans. A long-term financial plan can link to these other plans to provide a more complete perspective on a government’s financial situation. Perhaps the most obvious is the potential for long-term capital infrastructure investment plans to help inform future debt affordability or the capacity to fund infrastructure maintenance. Another possibility might include long-term land use plans, which might shed light on the size of the taxbase in the future or the population the government will serve. Other plans may also highlight important risks. An emergency management plan might highlight risks that could disrupt finances.

Finally, a long-term financial plan and forecast does not have to be a standalone “product.” It could be that all elements we just described are integrated into strategic planning and/or the budget process.

5. Develop the Capacity for Public Engagement

Considers trade-offs in how resources will be used and build or maintain the legitimacy of the local government in the eyes of its stakeholders.

The budget officer must design a budget process that: 1) considers trade-offs in how resources will be used; and 2) builds or maintains the legitimacy of the local government in the eyes of its stakeholders. High-quality public engagement can support both objectives. However, high quality public engagement requires specialized skills that might not match the skills and interests of existing staff. The resources may not exist to create a permanent, new capacity in the budget office.

So how might this capacity be created?

- The budget office could work with other people within local government who are skilled at public engagement. A public information or communication department could support public engagement. Community development planners also may have background or experience with public engagement.

- Employees across multiple departments could dedicate time outside their normal duties to build their skills for public engagement through dedicated training. When a department needs help, they can call on that internal group for assistance.

- A local government does not have to rely on its employees. Examples of outside resources include universities, survey research firms, community foundations, philanthropic groups, other local governments, consultants/professional facilitators, and civic organizations.

Another option is to build skills or expertise with a specific, high-quality public engagement method, tool, or technological platform. This provides a baseline for developing public engagement opportunities that go beyond the standard, legally required public hearing.

The best use of public engagement may change each budget cycle, as community conditions change. We will discuss this more later in this series.

Finally, public engagement includes the ability to communicate information to the public. This requires making complicated financial information more understandable to the nonexpert citizen. It also includes communication with members of the public who provided input into the budget. Showing them the positive results of their input may help develop networks of supporters who will help local government in the future.

6. Build Networks with Outside Organizations

Local governments can address complex community challenges more effectively by building collaborative networks with public, private, and nonprofit organizations, which requires teamwork beyond just the budget officer’s role.

The challenges that communities face often cannot be addressed by a single government. A single local government may not have the authority, capacities, and/or resources. By cooperating with other organizations (public, private, and/or nonprofit) and building networks of people with an interest in solving the same problem, a local government can bring more resources to address community challenges than by working alone. In this way, the network becomes a resource multiplier beyond what the local government can bring via its own budget. That said, we must recognize that building these networks are:

- An advanced form of public budgeting; and

- Not something the budget officer can do alone. You can access GFOA’s research on how to form networks here, which is focused on public finance applications.

For more research on using collaborative networks in public management, go here.